What does accountability mean when applied to the attempted genocide of Native people in the US? What does accountability mean as we watch reports of mass graves of First Nation children excavated in Canada? Over two thousand remains of Indigenous children have been found in these so-called “schools” thus far. What schools bury children on their grounds? That’s called a cemetery. Yet, cemeteries do not masquerade as schools for stolen children. Can you imagine being a child attending a “school” like that? Looking out the window during a grammar lesson at a killing field containing the remains of your classmates? Sitting down at your desk one morning with the seat next to you empty? Perhaps wondering if the child who was there the day before is now buried in the “school” grounds you walk over during recess?

What each child consciously knew varied, I’m sure. But as a survivor of organized abuse myself, in which I and other children and adults were tortured physically, sexually, and emotionally, I can tell you from personal experience growing up in a system of organized abuse that there are different ways of knowing. Children in situations like that tend to compartmentalize and at least partially block what is actually going on around them in order to survive. When I was in elementary school, I was sent to summer school across town because my father did not want to pay for a babysitter. One of the teachers at the summer school was a perpetrator in the sex trafficking ring I and others were used in. I knew I must never, ever acknowledge the group members outside of the group’s activities—namely, rape.

I rather doubt anyone who was in the room the first time I saw him at summer school would have noticed any change in my demeanor. Inside I felt fear, terror, and shock to see him in the summer school setting. I knew he belonged to that “other world” and I knew I absolutely could not show any sign of recognition. I also knew that if I messed up, and let on that I knew him, I would be in big, big trouble. In my world, that meant I, or my dog, or another child or family member would be badly hurt. Beaten. Whipped. Raped. Forced to eat rotted foods and then clean up our own vomit.

I ignored him. He ignored me. That was not the first time the two worlds overlapped in my life, and it would not be the last. When I saw him, my mind did not go further than knowing he belonged to that other world. My mind did not go into details about what could be done or had been done. My emotions did, but not my conscious mind. I could not have survived that. He and I carried on with our summer school roles. Outwardly, he was a friendly, gregarious man. He laughed and smiled a lot. He was a teacher and a coach. He was a leader. I told no one until over a decade later.

The perpetrators and those complicit with the abuses at the boarding schools did not rape and physically abuse children and then turn into an authentic kind, loving teachers the next moment. The abusers may have been able to compartmentalize. They may have been able to rape or kill a child at night and smile the next day, but a smile does not erase murder. A smile does not erase rape. A smile does not erase a culture of destruction. And a smile does not erase what that person is capable of doing the next night. At least some, if not many, of the children would have been aware to one degree or another what the school employees were doing to the children. They had to find a way to live with that, day in and day out, with no escape. It’s profoundly stressful.

In closed communities of rape and other violence, survival is instinctual. The abuse, the potential for abuse, and the emotions related to the abuse are pervasive throughout the community. Sometimes they simmer and sometimes they are on full-blast. At times the abuse is blatant, at times hidden, and at other times lurking, but the moral degradation of those committing these crimes pervades the institutions. The institutions themselves are morally repugnant, corrupt–rotten. The horror of the boarding schools and the thousands of Indigenous children secretly buried on their grounds is difficult to comprehend, even for those of us who have experienced the boarding schools or similar, organized abuse. It is mind-numbing. And then alarming. And then it makes one want to frantically run and move to escape the emotions. And if one does not find a way to heal, to calm the spirit, the horror cycles back into mind-numbing, or perhaps there is an outburst, or perhaps an act of self-harm or violence against another. Life is like riding a carousel, except you can’t get off and it doesn’t stop. Which horse will you ride today? The mind-numbing one? The frantic one? The angry one? Or will you make the choice to begin healing–to get off that carousel?

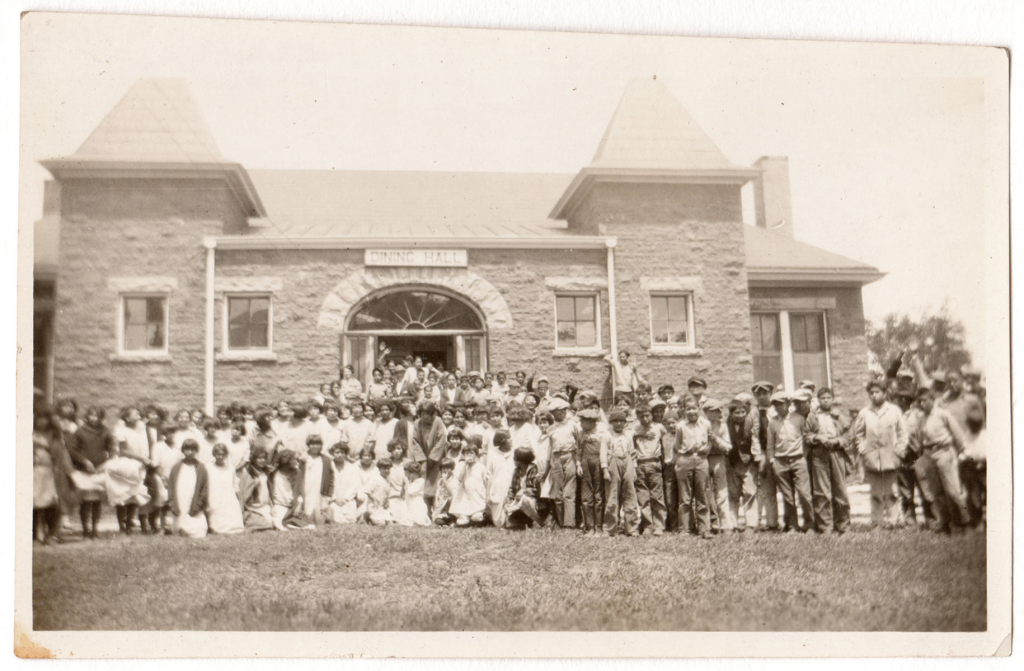

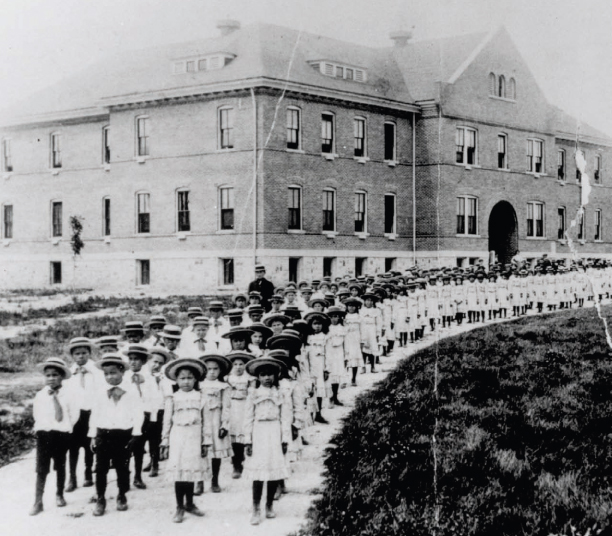

If we are honest, and we must be, we must reorganize how we think of the world, our country, the government, religious institutions, and the educational system. We must rearrange the myths of children as held, children as protected, children as precious that US and Canadian cultures project. We must replace those myths with the reality of the pervasive nature of the abuse of children historically and currently in the US and Canada, with the abuse of Indigenous children at the core of these colonial cultures. These boarding schools should be called what they were: organized, government-sponsored and church-run institutions of genocide.

In Canada and the US, there are many more “boarding school” grounds left to search for murdered Indigenous children. This news is stunning and traumatic, even though it’s been known and discussed in Indigenous communities for years. Finding these children’s bones in the ground, never returned to their family and tribes, is devastating to Native people, and to anyone with a heart and conscience. Indigenous people experience it as a collective trauma. The news of the graves, and those young children buried without ceremony, dying alone and frightened, in pain, without respect is deeply painful. It stirs not only our own pain from the abuses many of us have suffered in our lifetimes, but also the pain and trauma of our ancestors—some of whom are no more removed than our grandmother, or our mother, who set breakfast on the table for us when we were children.

What does accountability mean, what could it look like, for Native communities and our ancestors and those harmed in the cemeteries masquerading as schools? Canada and the US had identical policies toward the Indigenous people of Turtle Island. However, Canada is ahead of the US when it comes to uncovering the abuses in boarding schools. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (http://www.trc.ca/ ) documents that many of these “schools” starved, medically experimented on, raped, beat, denied languages and cultural traditions, and murdered First Nation children. Then they buried the children, some as young as three-years-old, like refuse on school grounds. The moment Canada announced it had discovered the first unmarked graves of First Nation children on the grounds of a boarding school, our communities were on fire again with pain and anguish. Our elders posted on Facebook what was done to them at these schools. Electroshock chairs in the basement. Food withheld. Rape of girls and boys. Forced labor, now called labor trafficking. Being kept apart from their families for years. Beatings. Forced conversion to Christianity. Beaten for speaking Indigenous languages. Being bought and sold for rape, now called sex trafficking. A Canadian elder abused at one of the so-called schools cried. She asked, “Why did they do that to us? We never did nothing to them.”

Evidence is mounting, making it harder and harder for the government and churches to continue to hide what they did. Deb Haaland, the US Interior Secretary, who is a member of the Laguna Pueblo people, has ordered an investigation into US boarding schools. Here in Minnesota, the governor just signed into law a Murdered and Missing Indigenous Relatives (MMIR) office. The return of the bones, skeletons, and sacred items that universities, museums, and individual “treasure seekers” have been digging out of Native graves for centuries to the tribes they were stolen from is gaining traction. It’s beginning, this thing called accountability, for the past and the ongoing abuses perpetrated against Native people. The wall of silence surrounding hundreds of years of violence committed by settlers and their institutions against Indigenous people on Turtle Island is crumbling. The babies are returning home.

This push for accountability is happening because of the work of Indigenous people. We are revealing the institutions and individuals harming and benefitting from the harm of Native children, women, men, and Two-Spirits. The government, churches, and corporations that created a country out of stolen land while putting Native people in the ground, are not stepping forward on their own to be accountable for their abuses–past or present. After all, of the five hundred treaties signed between the US government and tribes, five hundred were broken by the US government. Five hundred. So even as we celebrate these hard-fought accomplishments, some question whether we are to trust the MMIR office, the investigations into the boarding school graves, and this work to stop sex trafficking of Native women, youth, and Two-Spirits. We cannot confuse a smile—a gesture of sympathy or good will—with the extended, difficult work needed to create current and long-lasting change. We cannot allow a smile to act as a cover for the abuses those in power in this country committed and continue to commit against Indigenous people. Will the work be done with integrity and transparency? Will those committing these harms now be exposed and held accountable—no matter who they are? Will the work be conducted in such a way that will truly stop these abuses? Or will it simply be lip service?

Native people, especially women, have been working hard for hundreds of years to keep our people, families, and culture intact and alive despite the attempted genocide, assimilation, and death of 92% of the Indigenous population. We will continue to do so, but whether this time coming turns into a mass reckoning, a true movement accountable to healing and justice and truth, or whether it simply becomes yet another incidence in which some unfortunate information slips into the public consciousness for a minute or two and then is buried again, depends in part on what our friends and allies do to support Native resistance and calls for accountability.

I mentioned that at least some of those boarding schools also sold Indigenous children for rape. Guess who was involved? Church leaders. Government officials, Businessmen from the community. How will we hold the government, churches, and corporations accountable for past abuses of Native people? How will we hold those institutions accountable for their present maintenance, protection, and sometimes outright sex trafficking of Native women, youth, and Two-Spirit people? This country is still buying and selling and murdering Native children and youth for rape. It has not ended. Now is the time for accountability. Now is the time for truth. Now is the time for justice. What will you do?

St. Mary’s Mission in Red Lake began in some empty buildings on the reservation. The sisters converted an abandoned Hudson Bay Company’s warehouse into a school. In spite of its poor condition, the school opened with an enrollment of 25 day pupils. Years later when Sister Amalia was asked how they kept warm in that drafty house, she replied that they didn’t keep warm; they froze. The next spring they took in 27 boarding pupils in addition to the day students.

In the 1890s, Pipestone was illegally built by the federal government on Yankton Sioux reserved quarry land. In 1926, the Supreme Court resolved—in Yankton Sioux Tribe of Indians v. the U.S.—that the construction of the school violated the 1858 Treaty of Washington.

The Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School operated from 1893 to 1934, based on a social experiment by Lieutenant Richard Pratt in 1879. He took several Apache prisoners, cut their hair, taught them English, dressed them in military uniforms, and put them through a rigorous military-style training. While several men committed suicide, most learned English and “adjusted” to English-style traditions. Pratt considered this a success and successfully requested funding to offer all Native Americans a similar-style education. The result was the Indian boarding school system that the Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School was a part of.

—

“Accountability” is the second in a series of four blog posts about sex trafficking of Native women and youth in Minnesota, written by Chris Stark. Click here to read the first blog in the series, “A Feast and a Gift“. Click here to watch her story.

—

Chris Stark is Anishinaabe and Cherokee writer, researcher, and survivor. Her second novel, Carnival Lights, was just released. (See below)

“Fluid in time and place, Carnival Lights flows between one past and another, offering a heartbreaking portrait of multigenerational trauma in the lives of one Ojibwe family. This tapestry of stories is beautifully woven and gut-wrenching in its effect. Read it, and it may change you forever.” — William Kent Krueger, New York Times Bestselling AuthorBlending fiction and fact, Carnival Lights ranges from reverie to nightmare and back again in a lyrical yet unflinching story of an Ojibwe family’s struggle to hold onto their land, their culture, and each other. Carnival Lights is a timely book for a country in need of deep healing.

In August 1969, two teenage Ojibwe cousins, Sher and Kris, leave their northern Minnesota reservation for the lights of Minneapolis. The girls arrive in the city with only $12, their grandfather’s WWII pack, two stainless steel cups, some face makeup, gum, and a lighter. But it’s the ancestral connections they are also carrying – to the land and trees, to their family and culture, to love and loss – that shape their journey most. As they search for work, they cross paths with a gay Jewish boy, homeless white and Indian women, and men on the prowl for runaways. Making their way to the Minnesota State Fair, the Indian girls try to escape a fate set in motion centuries earlier.Set in a summer of hippie Vietnam War protests and the moon landing, Carnival Lights also spans settler arrival in the 1800s, the creation of the reservation system, and decades of cultural suppression, connecting everything from lumber barons’ mansions to Nazi V-2 rockets to smuggler’s tunnels in creating a narrative history of Minnesota.

“Chris Stark’s newest novel explores the evolution of violence experienced by Native women. Simultaneously graphic and gentle, Carnival Lights takes the reader on a daunting journey through generations of trauma, crafting characters that are both vulnerable and resilient.” — Sarah Deer, (Mvskoke), Distinguished Professor, University of Kansas, MacArthur Genius Award Recipient

“Carnival Lights is a heartbreaking wonder of gorgeous prose and urgent story. It propels the reader at a breathless pace as history crashes down on the readers as much as it does on the book’s vivid characters. The author’s brilliant heart restores their dignity and via the realm of imagination, brings them home.” — Mona Susan Power, author of The Grass Dancer, a PEN/Hemingway Winner

Learn more at www.ChristineStark.com

Carnival Lights can be ordered anywhere books are sold.

Carnival Lights